Ever since the worst financial crisis since the great depression, central bankers have been using unconventional means to manipulate economies to their will. Now, there is nothing wrong with unconventional thinking. Tackling a new problem, and asking ‘why not?’ is a useful and novel approach. Unfortunately, a novel approach to a problem when the stakes are so high could lead to unforeseen consequences.

Welcome to the great age of banker exploration, where central banks look for strange new lands in search of a magic formula to solve the low growth mystery. It’s an adventurous age, one with unknown perils at each new frontier. The lands discovered so far have weird names; ZIRP, QE, and now NIRP. Perhaps we’ve reached the final frontier. NIRP is a land where long held ‘rules’ are now opposite, it is a real world bizzaro land wrought with potential dangers.

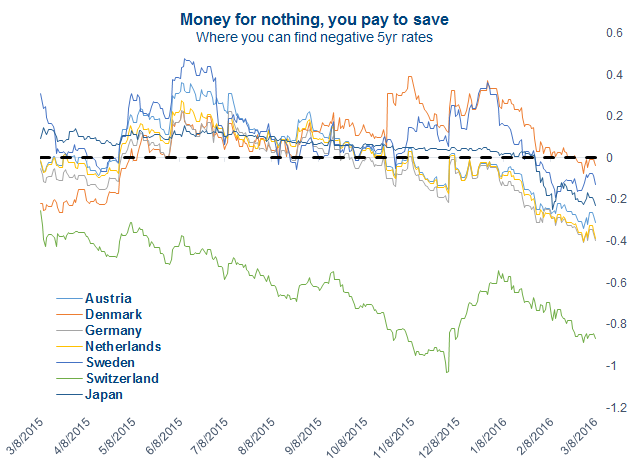

Up until relatively recently negative interest rates were relegated to economic academic papers. The very idea of a negative interest rate turns a fundamental principal of our capital market economy upside down. In June 2014, the European Central Bank (ECB) began paying -0.1% on deposits. The rate currently stands at -0.3%. Denmark and Switzerland have negative rates along with Sweden, and the Bank of Japan surprised markets earlier this year by also adopting a negative interest rate strategy. A full year and a half after the ECB ventured into the sub-zero realm in the hope that it will boost their economies, other central banks are starting to pay attention, the largest fear being that the Federal Reserve may one day venture into NIRP territory. In typical Fed fashion, little is being said besides that they are ‘studying’ the policy.

Up until relatively recently negative interest rates were relegated to economic academic papers. The very idea of a negative interest rate turns a fundamental principal of our capital market economy upside down. In June 2014, the European Central Bank (ECB) began paying -0.1% on deposits. The rate currently stands at -0.3%. Denmark and Switzerland have negative rates along with Sweden, and the Bank of Japan surprised markets earlier this year by also adopting a negative interest rate strategy. A full year and a half after the ECB ventured into the sub-zero realm in the hope that it will boost their economies, other central banks are starting to pay attention, the largest fear being that the Federal Reserve may one day venture into NIRP territory. In typical Fed fashion, little is being said besides that they are ‘studying’ the policy.

What it means?

Central banks provide a benchmark for all borrowing costs, setting their benchmark rate negative spreads to a range of fixed-income securities. By the end of 2015, over a third of the debt issued by euro zone governments had negative yields, and Japan recently had its first bond auction with negative rates. In very simple terms, it means that if you buy a government bond and hold it until maturity you will not get all of your money back.

Negative rates set by the central banks are applied to funds held by financial institutions at the central banks, including excess reserves. The belief is that the cost of holding excessive funds will create an incentive for banks to reduce their excess reserves, lend out more money which will in-turn bolster economic growth.

The whole concept as a whole is quite odd. Savers are to pay borrowers for the privilege of deferring consumption. Borrowers are the ones who get compensated for spending now. Remember the fable The Ant and the Grasshopper? The story illustrated the virtue of saving for the future. Today, the story would have a completely different ending. Since you now have to pay to save, the spend-free grasshopper is the one being rewarded at the ant’s expense.

Why it might work

A central bank’s monetary policy was more or less restricted to just raising or lowering their benchmark borrowing rates. When an economy was struggling, lower interest rates reduced the cost of capital and boosted economic activity. If inflation got out of hand, raising rates took the foot off of the gas pedal and acted more as a drag on economic growth. Currently, inflation is not a concern globally as ‘deflation’ is a much larger concern to developed nations, specifically Europe and Japan. Real interest rates in many developed nations are already negative, and the fear is if they push further into negative territory the chances of a solid recovery will be stifled.

It’s a little too early to tell if negative rates are having any real benefit. At first glance, it doesn’t seem to be having much benefit for European Consumer Price Index (CPI) measures. Then again, we don’t know what inflation would be today had the ECB not made deposit rates negative last year. Negative rates seem to be the only safe place from the ever-present threat of deflation. But they are not without their concerns. NIRP gives central bankers more room both for actual rates as well as for future guidance. This is important because if the belief was that zero was the lower bound, no amount of dovish language from central banks would be able to convince the markets that they had to tools to back up the talk. It also will create more room for further quantitative easing (if needed) to further depress long term borrowing rates.

Unintended consequences

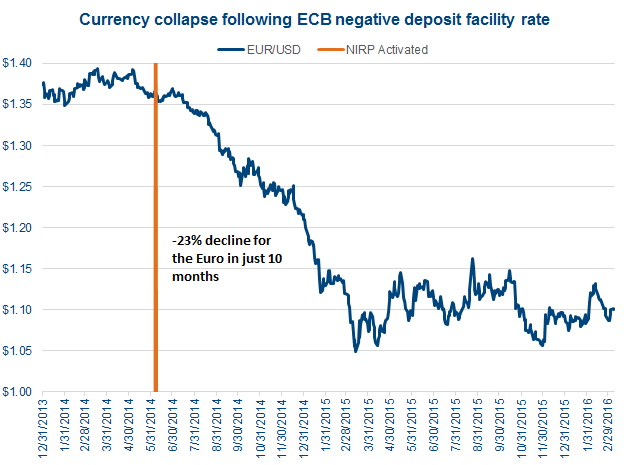

Driving interest rates progressively lower has some obvious consequences. One such consequence is adding further fuel to the race to the bottom between some major economies. Currency depreciation is just a symptom of the real problem: investors searching for higher yield and having to go global. The ECB moved their benchmark deposit rate into negative territory in June of 2014, since then the EURO has fallen –23% against the U.S. dollar. Falling currencies raise the price of imports which does help combat deflation and also helps domestic exporters.

Though not really an issue at present levels, at much even lower rates the demand for hard currency would increase. This would really only occur if rates went low enough for banks to flow through the negative rates to retail clients. In this scenario, in-home safes would become a normal purchase for every household, gift cards with no expiry would be popular as well. It would be a time when we’d love to pay debts quickly and extend the amount of time debtors have to pay you back. There is also the theory that cash will simply be phased out. First would be the elimination of large denomination banknotes, then progressively smaller bills will be eliminated. Conspiracy theorists are already at work saying the recent talk about the abolishment of high denomination bills to fight laundering and terrorism is really just step one to eliminate cash. Another theory is a simple tax on money, known as a Gesell tax which makes the difference between cash and electronic money indistinguishable.

Simply holding onto cash means an implicit interest of zero, so any rational individual would do just that. The problem is that the theory breaks down when you’re not dealing with individuals with relatively small balances. Recent experiences show that the lower bound is not in fact zero. There are few reasons for this. Firstly, there are costs associated with obtaining, transporting and securing large amounts of cash. If you’ve watched the Netflix series Narcos you can appreciate the challenges large amounts of cash can create. Secondly, there simply is not enough hard currency available for this to be a viable option for everyone.

The transmission of negative rates to retail banking clients remains a divisive issue. There is the potential for political backlash which would likely be material. So far, there is a divergence between the retail and wholesale banking markets which will likely widen the further rates fall below zero. Corporate deposit rates have already moved below zero in Denmark, but these not been passed on to retail deposit rates.

The lowest bound

The financial sector as a whole is at risk with negative rates, profit margins will continue to be compressed as yield curves flatten net interest rate margins fall. We’re seeing this already for European banks profits, as the recent selloff has put the security of many of them in question. Insurers and pension plans will also face huge hurdles to fund future liabilities if they are unable to find safe stable positive yield. Negative interest rates have the potential to do a lot of damage to households worldwide. Even at the individual household level retirement and education savings can and will be slowly eroded if rates go low enough. At some yet unknown rate, the stability of the financial system itself would be put into question as the demand for hard currency and margin compression will rise squeezing banks even further.

Central bankers seem intent on going lower, ignorant it seems of the many risks. Narrow mandates coupled with the power and creativity to venture into unexplored territory is a risk. One thing is certain, as long as rates remain negative, future savers will be hurt by extremely low expected rates of return. The once crazy helicopter money theory put out by Ben Bernanke might be next, if negative rates can’t even do the trick to spur growth.

Bringing NIRP closer to home

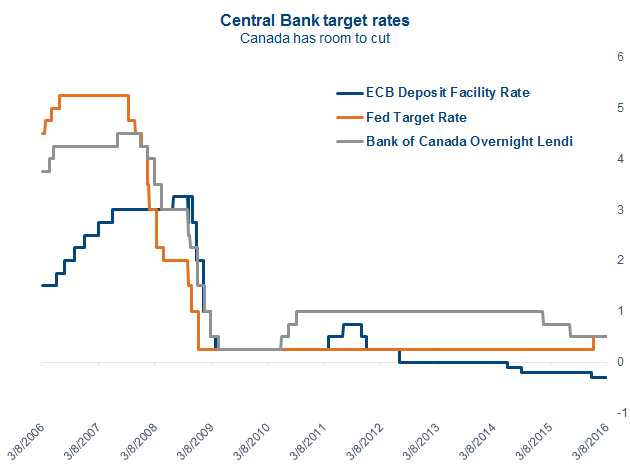

Can Canada be next for unconventional monetary policies? We might only be an unforeseen global shock (U.S. stock market crash, China hard landing) away that would put the Canadian economy into a tailspin. As the cyclical back drop is already quite weak, and rates are not far off of zero, the possibility certainly exists, though barring a housing collapse, the likelihood is slim.

Inflation is still around 2% annualized, GDP growth is positive again. Bottom Line: Unconventional monetary policies such as negative rates are unlikely in the near future, as there is still room to lower rates.

That doesn’t mean that negative rates around the globe will not have an impact. Government bond spreads can only be stretched so far. Falling rates in Europe will likely be translated to low fixed income rates here for some time. The search for yield will continue, sometimes venturing down into questionable assets. Investors must focus on income sustainability, and the underlying fundamentals of a business and not be tempted by just high yield.

In conclusion

With the Fed having begun to raise their rates, and the Bank of England continuing to hint to future hikes we expect the divergence in central bank policy to continue to widen. This will likely bring further currency volatility around the globe. Though the risks are considerable, delving further into negative territory in Europe and Japan only adds to market stresses at the moment. In the race to the bottom, bankers are not likely to stop unless the political backlash grows louder. The ECB seems intent on innovation, we just hope that they do so by balancing the risks of large scale cash withdrawals and minimizing the risk to bank profits, while attempting to maximize the incentive for banks to lend.

Charts are sourced to Bloomberg unless otherwise noted.

This material is provided for general information and is not to be construed as an offer or solicitation for the sale or purchase of securities mentioned herein. Past performance may not be repeated. Every effort has been made to compile this material from reliable sources however no warranty can be made as to its accuracy or completeness. Before acting on any of the above, please seek individual financial advice based on your personal circumstances. However, neither the author nor Richardson GMP Limited makes any representation or warranty, expressed or implied, in respect thereof, or takes any responsibility for any errors or omissions which may be contained herein or accepts any liability whatsoever for any loss arising from any use or reliance on this report or its contents. Richardson GMP Limited is a member of Canadian Investor Protection Fund. Richardson is a trade-mark of James Richardson & Sons, Limited. GMP is a registered trade-mark of GMP Securities L.P. Both used under license by Richardson GMP Limited.