I must admit that I did a double take when I read the headline last week stating that Germany, the country that was home to much of the initial development of the internal combustion engine, has taken steps to phase out and eventually stop the sale of new combustion engine vehicles by 2030. It seems like a very heavy-handed approach to legislate a specific technology out of use, especially a technology and industry that has been a driver of the German economy since the Second World War. German car companies continue to produce some of the most advanced cars in the world. I wonder if Gottlieb Daimler, Karl Benz and Rudolph Diesel would have ever dreamed that their government would take steps to eliminate their revolutionary invention from use in the future.

Regardless of your view on the environment and this technology, we should acknowledge that the internal combustion engine certainly had a good run in the past 130 years and fundamentally changed modern life.

The year 2030 seems like a long way off, but 14 years can pass quite quickly. In last month’s blog post I analyzed Alberta’s proposal to legislate in 30% renewable power in the province by the year 2030. The Paris Climate Agreement was agreed upon by 195 countries in late 2015 and politicians are now working to find ways to meet the terms. Not to sound too cynical, but I doubt that many of the law makers in office today will still be serving 14 years from now. It is still early days for this policy, as this German proposal still needs to be adopted across the European Union (EU). However, Germany has historically set the trend for laws in the EU so it is likely that some form of it will make its way through the EU system and into law across the continent in the coming years.

Did Volkswagen’s scandal involving their vehicles cheating American emissions tests have anything to do with this new heavy-handed regulatory approach that is being proposed? While Volkswagen covertly programming a control chip to turn off the emissions controls systems went undetected for years, it would be more challenging to fake the fact that a car has a gasoline engine and fuel tank as opposed to an electric motor and batteries. It is also ironic that the German government is forcing their own auto industry, the fourth largest automotive market in the world, to play catch-up with Tesla, the Silicon Valley based electric vehicle producer, and is forcing them to produce their own ‘zero-emission’ cars. Perhaps it is the German legislators finding some way to put Volkswagen in the penalty box for their emissions cheating shenanigans.

This policy may eliminate the intermediate technologies, such as plug-in hybrid cars that are significantly more efficient and are coming to market this year. This type of car was written about in an earlier blog where it was detailed how they have some strong advantages in range and practicality for long distance travel but consume little fuel in day to day driving.

If the 2030 deadline date stands as a firm date when no further combustion engine vehicle sales are allowed, then automotive manufacturers will need to ramp up electric vehicle production well before that. This proposed legislation would affect not only the German automakers, but any automaker that sells cars in the European market, which is basically every major automotive manufacturer on the planet.

It will take some time for the current fleet of vehicles that is on the road today to wear out and work through their useful life. The average age of a vehicle on the road today in North America is approximately 12 years old. It will therefore take a few decades after the 2030 date to eliminate combustion engine cars from the roads. The change won’t happen overnight and there will likely be exceptions for specialty cars and antique cars that will remain on the road for some time.

Currently, the top selling electric cars on the market are the Nissan Leaf, which is affordable but limited by a range of only ~120km, and the Tesla Model S that has a good range of over 400km, but costs over $75,000 for a base model. Basically, the options for electric vehicles are a cheap car with a barely functional range or an expensive car with a pretty good range that is out of the price range of many buyers. Automakers will clearly need to offer a much broader range of vehicles for this to allow for widespread adoption.

Chevrolet’s all electric Bolt is scheduled to start production this month and Tesla’s much hyped and more affordable model 3 is set to hit the markets next year, if Tesla can hit their ambitious production target. Both of these cars have a stated range of over 350km and are priced at around USD $30,000-$35,000. If these vehicles deliver on their promised range and price point, they should have much broader appeal than the current electric vehicle offerings on the market. It appears that we are witnessing the beginning of the end of the combustion engine, whether by market forces or government intervention.

In the past, we have seen legislation successfully phase out the use of CFC’s to protect the ozone layer and the implementation of scrubbers on factory and power plant smoke stacks to reduce sulphur emissions in order to eliminate acid rain. When I was in elementary school, these two issues were arguably some of the biggest environmental problems of the day. Throughout my upbringing, teachers and text books drove fear in the minds of children that one day there would be no ozone left and we would have to wear sunscreen every day of the year to go outside. Acid rain was supposed to destroy historical limestone buildings, statues and forests in the coming decades, but fortunately neither of these events came to pass. The elimination of these two forms of pollution was successful, but it was a much less ambitious plan than what legislators are proposing regarding the internal combustion engine.

The elimination of the internal combustion engine in Europe has broad implication for industries around the world. If this policy is implemented fully in Europe and other jurisdictions around the world, it will force all automakers to completely revamp their vehicle line-ups.

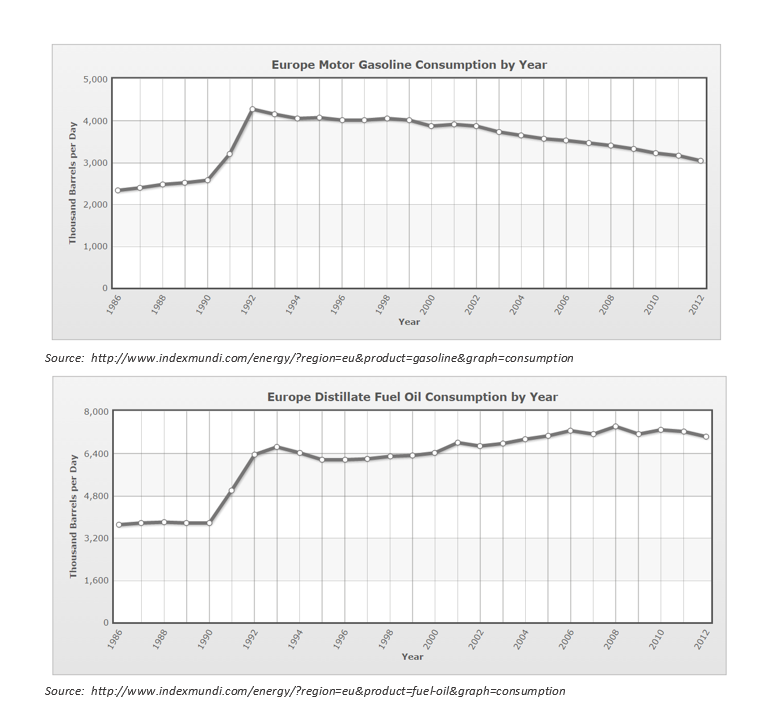

This legislation also has significant implications for the energy industry. Europe consumes approximately 10 million barrels per day of gasoline and distillate/diesel fuel combined, and demand for fuel has already been falling for the past decade. This market represents about 10% of global demand for fuel. Phasing out the combustion engine has not yet been proposed at a national level in the United States, but Ontario appears to be leading Canada in this direction with their proposed goal to have over 5% of new cars sales to be electric in the province by 2020. While this is clearly a far less ambitious plan than Germany’s complete phase out, it is a small step in the same direction. North America consumes about 20 million barrels per day of oil, and if we follow this European model the demand for oil could fall significantly.

What will these graphs look like if the European continent phases out the internal combustion engine?

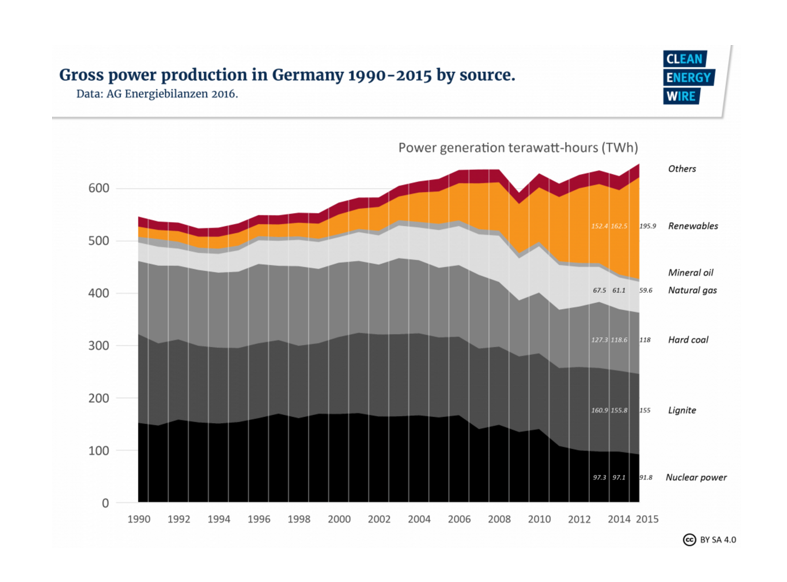

But how is Germany’s electricity generated?

Germany currently generates about 55% of its electricity from coal and natural gas, so switching to a ‘zero-emission’ electric car isn’t truly a ‘zero-emission’ solution as about half of the electricity will come from sources that still produce emissions. It is impossible to segment the electricity in the transmission lines and decide that you want only the ‘green electrons’ to be the ones that you charge your car with. Although I should note that renewables have increased their contribution significantly in the past few years. If the trends in Germany continue for both the increase in renewables as part of their electricity mix and the decrease in direct fossil fuel consumption, Germany will likely meet its Paris agreement targets. Though I can only speculate at what cost it will be to their economic productivity.

Regardless of whether this new law proposed by Germany is too heavy-handed and damages their own economy, if it is implemented and adhered to, it will have significant implications on the consumption of fossil fuel in the next two decades. Perhaps all of the fuss and protests over building new oil pipelines will be wasted effort, as they may not even be needed in the future.

The opinions expressed in this report are the opinions of the author and readers should not assume they reflect the opinions or recommendations of Richardson GMP Limited or its affiliates. Assumptions, opinion and estimates constitute the author’s judgement as of the date of this material and are subject to change without notice. We do no warrant the completeness or accuracy of this material, and it should not be relied upon as such. Before acting on any recommendation, you should consider whether it is suitable for your particular circumstance and, if necessary, seek professional advice. Past performance is not indicative of future results. The comments contained herein are general in nature and are not intended to be, nor should be construed to be, legal or tax advice to any particular individual. Accordingly, individuals should consult their own legal or tax advisors for advice with respect to the tax consequences to them, having regard for their own particular circumstances. Richardson GMP Limited is a member of Canadian Investor Protection Fund. Richardson is a trademark of James Richardson & Sons, Limited. GMP is a registered trade-mark of GMP Securities L.P. both used under license by Richardson GMP Limited.