The Federal Reserve delayed cutting rates this week while ignoring signs of a pending recession. The U.S. economy is slowing rapidly and there is a multitude of clues that the U.S. will enter recession before the end of this year.

The Federal Reserve has yet to cut rates, but that first cut is almost certainly coming in September. There is a possibility that the Fed could move even faster than that, but that would require a special meeting of the Open Market Committee. The Fed would only do that if there are clear signs that a recession has already started.

The unemployment rate increase since mid-2023 is already signaling that the U.S. is in a recession now, or about to be in one.

Other recent economic reports are showing that a recession in the near future is highly probable or has started already.

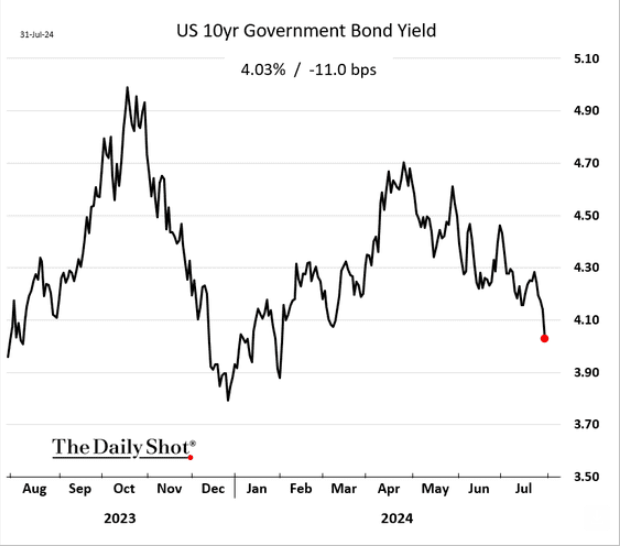

For example, a sharp drop in the US 10-year government bond yield is a hint that there is a period of weakness coming to the economy.

This sudden drop in longer-term interest rates has happened without any influence that the Federal Reserve might have. Investors park their money in government bonds when they think that an economic slowdown is coming, and they have decided to reduce their investment risk. So they sell equities (and other risky assets) and buy government bonds.

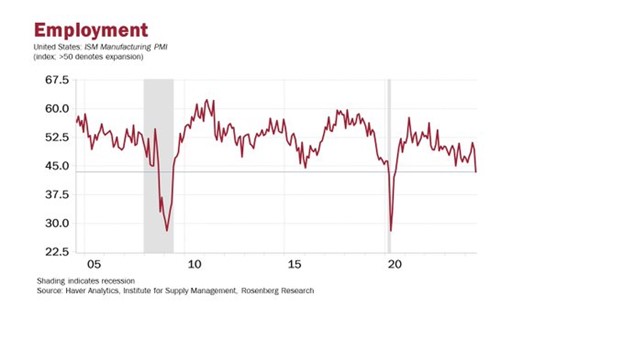

A very weak ISM manufacturing PMI number came out on Thursday August 1, dropping to 46.8. Any number below 50 indicates contraction in manufacturing. The ISM sub-index that shows employment was even weaker at 43.4.

As David Rosenberg of Rosenberg Research, @EconguyRosie, points out, this is the weakest employment reading since June 2020 and lower than September 2008 when Lehman Brothers collapsed:

When a recession has been identified policy interest rates will come down, as the Fed will cut rates several times in a short period. Or the Fed might do a larger than 25 basis point cut to get caught up with the weakness.

But the other policy lever — fiscal spending — is more important than small moves in interest rates. And changes in those policies are unlikely during the current election cycle that goes until November 5.

In fact, it is sobering to ponder the fact that the economy could be faltering badly when the U.S. government is spending at record high levels while collecting so much less in income tax receipts.

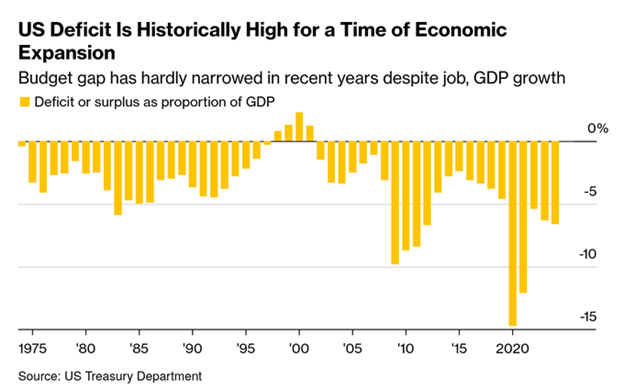

Here’s the annual fiscal deficits over the last half-century as a percent of GDP:

During the Global Financial Crisis (08-09) the deficit went very high; greater than 5 percent for four years. And again in 2020-21, when the COVID-19 crisis hit, the fiscal deficit soared to more than 10 percent for two years.

From 2022, a period of substantial growth, the deficit stayed above 5 percent. And, in just four years, the U.S. debt grew $12 trillion to $35 trillion.

The next few years will be very challenging for policymakers, as they enter a recession with such large deficits.

Hilliard MacBeth

The opinions expressed in this report are the opinions of the author and readers should not assume they reflect the opinions or recommendations of Richardson Wealth or its affiliates. Assumptions, opinions and estimates constitute the author's judgment as of the date of this material and are subject to change without notice. We do not warrant the completeness or accuracy of this material, and it should not be relied upon as such. Before acting on any recommendation, you should consider whether it is suitable for your particular circumstances and, if necessary, seek professional advice. Past performance is not indicative of future results. The comments contained herein are general in nature and are not intended to be, nor should be construed to be, legal or tax advice to any particular individual. Accordingly, individuals should consult their own legal or tax advisors for advice with respect to the tax consequences to them, having regard to their own particular circumstances.. Richardson Wealth is a member of Canadian Investor Protection Fund. Richardson Wealth is a trademark by its respective owners used under license by Richardson Wealth.