The Bank of Canada (BOC) held interest rates steady at 5 percent in January, highlighting growing weakness in the Canadian economy.

But unfortunately, inflation is not declining as fast as the central bank would like.

Will the central bank abandon its inflation target?

While the weakness in the economy would normally allow the Bank of Canada to make a preemptive rate cut to stimulate the economy, CPI inflation of 3.9 percent in 2023 will make that action difficult to justify. After all, the central bank, along with most other central bankers, have one main task, to control inflation. And inflation is not even close to the official target of 2 percent which Canada adopted in 1991.

At 2 percent the currency loses about one-half of its purchasing power in 36 years, which some say is far too high to maintain the purchasing power of the currency. At 4 percent it would only take 18 years.

How did Canada get locked-in to a 2 percent inflation target?

An 2014 article from the New York Times explains the origin of the target.

The story starts in New Zealand in 1989. For most of the 1970s and the early 1980s inflation all over the developed world had been a big problem. So New Zealand passed the Reserve Bank Act of 1989 which directed the finance minister and the head of the central bank to set an inflation target and guide interest rates to meet that target.

The two percent level came from a chance remark by a former finance minister who suggested that inflation should zero percent. But others, such as real estate developers and union leaders, were against using any target.

As a compromise, sheep farmer Don Brash, the newly appointed head of the central bank, thought they should expand the range and use 2 percent as the upper band.

So, a country of 3.4 million people, with more sheep than people, started a radical experiment — committing to an inflation target. And it worked! From 1989 when the target was adopted to 1991 inflation declined from 7.6 to 2 percent. Central bankers noticed and started to follow with Canada adopting 2 percent in 1991.

Some argued that 2 percent was too high, and zero to 0.5 percent would be better as the soundness of money would be protected. Others, like Janet Yellen of the Federal Reserve, suggested that some inflation is good as it greases the wheels of the economy.

Now, in 2024, after another serious bout of high inflation, central bankers give no hint of dropping the 2 percent target.

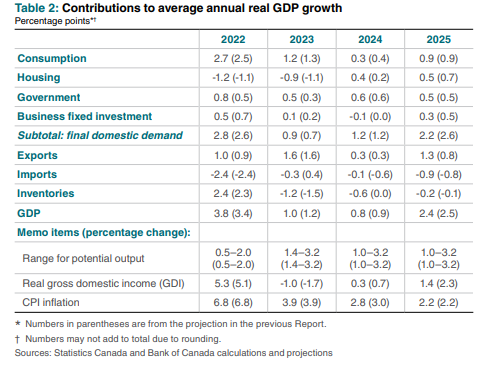

And that puts the Bank of Canada in a tough spot as the economy is weak and getting weaker. The BOC forecasts growth of 0.8 percent for 2024:

So, Canada’s GDP will likely be negative in 2024 triggering the official recession designation and the Bank of Canada will have to decide whether to abandon the 1989 New Zealand benchmark for inflation.

A very difficult choice.

Hilliard MacBeth

The opinions expressed in this report are the opinions of the author and readers should not assume they reflect the opinions or recommendations of Richardson Wealth or its affiliates. Assumptions, opinions and estimates constitute the author's judgment as of the date of this material and are subject to change without notice. We do not warrant the completeness or accuracy of this material, and it should not be relied upon as such. Before acting on any recommendation, you should consider whether it is suitable for your particular circumstances and, if necessary, seek professional advice. Past performance is not indicative of future results. The comments contained herein are general in nature and are not intended to be, nor should be construed to be, legal or tax advice to any particular individual. Accordingly, individuals should consult their own legal or tax advisors for advice with respect to the tax consequences to them, having regard to their own particular circumstances.. Richardson Wealth is a member of Canadian Investor Protection Fund. Richardson Wealth is a trademark by its respective owners used under license by Richardson Wealth.