History will judge that the long period of low interest rates, which endured from 2009 to early 2022 was a colossal mistake. Investors piled into fixed income assets that were extremely overpriced based on rates close to zero. And now most assets that are sensitive to rates are repricing sharply downward.

Last week we saw China’s second largest property developer, China Evergrande, abandon its attempt to restructure US$30 billion of debt. Institutional lenders all over the world are wondering if they will see any funds returned to them.

An 83-story office tower in Chicago’s East Loop, the AON Center, was purchased by 601W in 2018 for US$780 million. Credit ratings firm Morningstar reported that its recent value as $414 million, well below the $536 million loan issued for the purchase. The owner is now in default on that loan and might lose the building to the lenders.

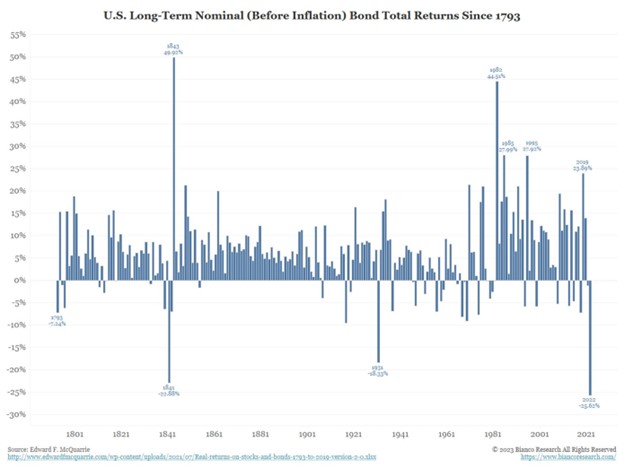

A much more important asset class, the U.S. government bond market, has lost substantial value for two years in a row. This has only happened a couple of times before in the entire history of the U.S. government bond market back to 1793.

It seems clear that four decades of excellent gains in the bond market, that started with the 44.51 percent return in 1982, are now over and we can expect, at best, to earn our coupons from here on.

The 25.62 percent loss in 2022, at the far right of the chart, was the worst single year loss in more than two hundred years. And 2023 is not doing great, at minus 8.5 percent so far.

In the category of “what were they thinking?” we can only wonder about investors, mostly pension plans, that piled into the “century” bond issued by the Austrian government that matures in 2117. On the issue date this 100-year offering was 4 times oversubscribed as investors were hungry for the yield of 1.171 percent. At that time there were very few bonds that yielded higher than 1 percent.

This price decline is spectacular:

The paper loss, close to 75 percent, is unlikely to be recouped as the tiny annual interest rate payments will never make up for the capital loss.

The tulip bulb mania, where people paid enormous sums for tulip bulbs in Amsterdam from 1634 to 1637, is another well-known story of speculative folly.

Allegedly, the peak in the 3-year bubble occurred when a bulb of the coveted Semper Augustus flower traded for the same value as a mansion in the most exclusive district.

Fortunes were won and lost during that period of irrational exuberance, described in “Extraordinary Popular Delusions and the Madness of Crowds,” by Charles Mackay, published in 1841.

The recent period of interest rate mania could be much more important for world financial markets as trillions of dollars are based on these interest-sensitive assets which were, until recently, considered to be safe havens. Few investors realized that they were speculating on low rates lasting forever, but they were.

Hilliard MacBeth

The opinions expressed in this report are the opinions of the author and readers should not assume they reflect the opinions or recommendations of Richardson Wealth or its affiliates. Assumptions, opinions and estimates constitute the author's judgment as of the date of this material and are subject to change without notice. We do not warrant the completeness or accuracy of this material, and it should not be relied upon as such. Before acting on any recommendation, you should consider whether it is suitable for your particular circumstances and, if necessary, seek professional advice. Past performance is not indicative of future results. The comments contained herein are general in nature and are not intended to be, nor should be construed to be, legal or tax advice to any particular individual. Accordingly, individuals should consult their own legal or tax advisors for advice with respect to the tax consequences to them, having regard to their own particular circumstances.. Richardson Wealth is a member of Canadian Investor Protection Fund. Richardson Wealth is a trademark by its respective owners used under license by Richardson Wealth.