A $12.5 million investment in clean energy earned an “accidental” profit of $200 million from a blank-check company. Here is how that works.

Blank-check companies -- SPACs or Special Purpose Acquisition Companies -- are proliferating, a strong signal that this market has gone wild.

Blank-check vehicles are shell companies used to take a private company public while bypassing the normal requirements for a stock market listing. Along the way many people gain substantial riches, sometimes without taking any risk.

Even institutional investors, like AIMCO and the Health Care of Ontario Pension Plan, are getting involved in this hot market. One of the largest funds to participate is Saudi Arabia’s $300 billion Public Investment Fund.

One attractive feature of a SPAC for the investor is the ability to withdraw one’s investment before a deal is completed after the announcement. The SPAC has up to two years to complete an acquisition or find a merger target. Day traders and pension plans alike are speculating on these shell companies which are pursuing targets in green energy or financial technology or other hot sectors.

Once the announcement of the target company is made, shares in the shell company often soar higher even before deal is completed. Speculators will sell their shares in the shell company during that period.

For example, Social Capital Hedosophia Holdings Corp announced it is combining with Social Finance Inc. The shares of the shell company went up 63%, even though its only asset is cash and a stock market listing. SoFi is a member-centric, one-stop shop for financial services with $1 billion of revenue. After the announcement SoFi is valued at $8.65 billion.

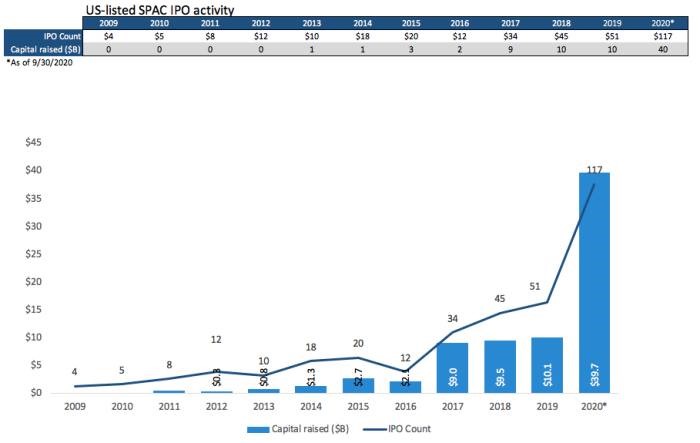

The number of blank-check companies ballooned last year signaling that this stock market has moved into the speculative phase.

Source: Bloomberg

Some people have earned fortunes. Jeremy Grantham, the investor featured in last week’s note on the market, invested years ago in a solid-state battery project at Stanford University. Grantham, already a billionaire, is involved in funding research into climate change. One of his investments helped start a company called QuantumScape. From his $12.5 million stake, he received a $200 million profit when QuantumScape went public with a blank-check company - Kensington Capital Acquisition Corp.

Grantham told the Financial Times, “This is unlike anything else in my career. This was by accident the single biggest investment I have ever made. It gets around the idea of listing requirements … But I think that it is a reprehensible instrument and very, very speculative by definition.” The merger valued QuantumScape at $3.3 billion but after the announcement the shares quintupled to $16 billion. QuantumScape is expected to produce solid-state batteries for electric vehicles later in this decade but there are no guarantees of success.

Grantham claims that this market bubble has “matured into a fully-fledged epic bubble.” He compared this 12-year run to 1929 and the South Sea Bubble in the 17th century.

Another investor with a great track record is Gary Shilling. He also compared this market with bubbles in the 1700s in his latest Insight. One case in 1720 was the promoter who advertised “A company for carrying on an undertaking of great advantage, but nobody to know what it is.” He required investors to commit 2% of their investment immediately, with the balance due in a month when details of the project would be announced. In one day, he took in a fortune from greedy people who lined up for hours to invest with him.

But that night the promoter disappeared, with all the money, leaving people to wonder what the project was.

Hilliard MacBeth

The opinions expressed in this report are the opinions of the author and readers should not assume they reflect the opinions or recommendations of Richardson Wealth or its affiliates. Assumptions, opinions and estimates constitute the author's judgment as of the date of this material and are subject to change without notice. We do not warrant the completeness or accuracy of this material, and it should not be relied upon as such. Before acting on any recommendation, you should consider whether it is suitable for your particular circumstances and, if necessary, seek professional advice. Past performance is not indicative of future results. The comments contained herein are general in nature and are not intended to be, nor should be construed to be, legal or tax advice to any particular individual. Accordingly, individuals should consult their own legal or tax advisors for advice with respect to the tax consequences to them, having regard to their own particular circumstances.. Richardson Wealth is a member of Canadian Investor Protection Fund. Richardson Wealth is a registered trademark by its respective owners used under license by Richardson Wealth.