The price of crude oil (WTI) plummeted from a peak in early October of more than $75, to a bottom near the end of December below $45. This rapid plunge was surprising as OPEC announced production cuts of 1.2 million barrels per day and even Alberta kicked in with government-mandated cuts of 300,000 barrels per day.

What are the most likely reasons for this precipitous plunge in the price of oil?

The most oft-mentioned reason, on the demand side, for this price tumble is the possibility of a 2019 US recession. It makes sense to worry about oil if there’s a recession because we know that oil demand takes a big hit, up to 2M barrels per day, during a recession. Unemployed people drive their cars less while younger people delay buying a car. But, somehow, that doesn’t explain what happened given that a recession was not really on anyone’s planning horizon when the slump occurred.

What about excess supply? While OPEC announced an agreement to cut production in early December perhaps the world had been producing way too much oil.

Most analysts mention the US shale revolution causing upheaval in markets. At the end of 2017 all three international agencies, (IEA, EIA and OPEC) forecast about 1M barrels per day increase from the US.

2018 growth turned out to be double that, reaching 2M barrels per day. Ongoing innovation and technological improvements allow producers, especially in the Permian shale in Texas to continue to surprise everyone with the amount of new production they deliver.

Another explanation for the crude price crash is the forced liquidation of speculators. As a commodity, crude oil is essential to our lives, especially in transport. But in the toolbox of derivatives traders WTI crude is one of their largest trading contracts for finding profits and losses. And, at the end of 2017, the amount of speculation on the long side in the crude oil contract was at record highs. It has now been reduced to more normal levels.

Could it be Tesla? Electric vehicles are gaining in popularity and they don’t use any crude at all. But Tesla by itself might reach 1 million new cars per year by 2020, which would be a huge success story for Tesla but not enough to change the demand supply balance for crude. There are about 1 billion vehicles worldwide, including cars, trucks and buses consuming gasoline, diesel or benzene or gasoil. 88 million new vehicles were sold in 2018, almost all powered by fuel.

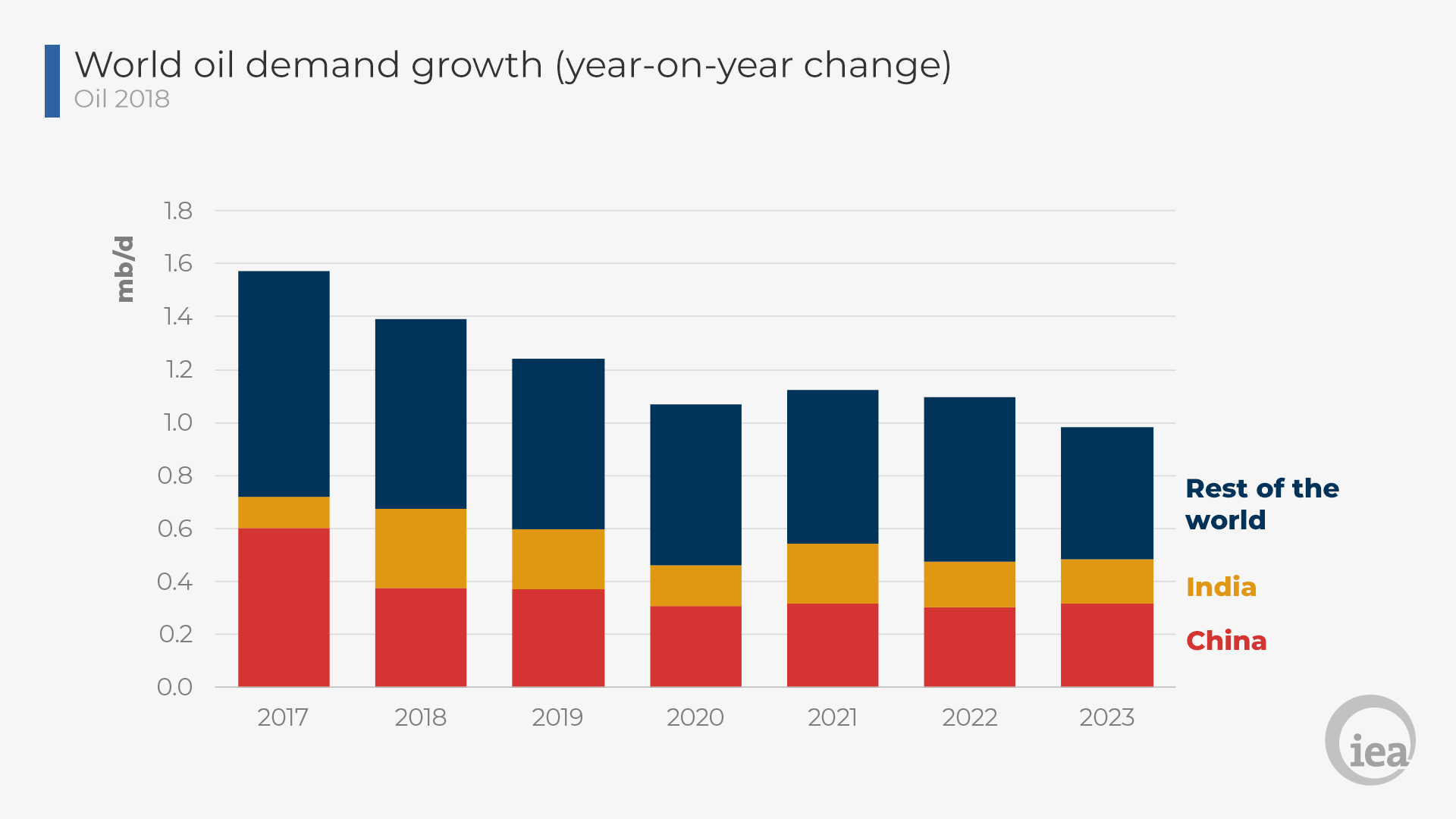

But one key to future demand growth for crude oil is in emerging markets. About ½ of all growth in demand for crude oil was going to come from China and India as they embraced the North American ideal of gasoline-powered car mobility.

Source: International Energy Agency

But what if the biggest car market in the world, China, were to decide to embrace electric? In mid-2018 China announced a new set of incentives and subsidies that increased subsidies on electric cars that go more than 180 miles per charge. Quotas require that all manufacturers with greater than 30K per year in sales must sell at least 10 percent in New Energy Vehicles (NEV).

The stated goal is to have NEVs make up 20 percent of all sales by 2025. It’s not hard to imagine how much scrambling there will be among Chinese manufacturers as well as Tesla, Daimler, GM, Ford and others to get in on this action.

Here’s a description of just one company, SAIC:

State-owned, publicly listed SAIC Motor Corp Limited is China’s largest car maker and top vehicle exporter. It operates assembly plants for Volkswagen and GM, producing a total of 6.93 million cars per year. The company started operations in 2006 by purchasing the British MG Rover car platform. The company plans to sell 120K NEVs in 2018 and 600k in 2020.

There are at least nine other major Chinese companies entering the electric car market, with plans to export to the world.

China imports and consumes more oil than any other country at about 11 million barrels per day. A move to electric vehicles would fit nicely into several themes for the emerging giant’s plans. And that would put a big hole in plans for future oil demand.

Hilliard MacBeth

The opinions expressed in this report are the opinions of the author and readers should not assume they reflect the opinions or recommendations of Richardson GMP Limited or its affiliates. Assumptions, opinions and estimates constitute the author's judgment as of the date of this material and are subject to change without notice. We do not warrant the completeness or accuracy of this material, and it should not be relied upon as such. Before acting on any recommendation, you should consider whether it is suitable for your particular circumstances and, if necessary, seek professional advice. Past performance is not indicative of future results. The comments contained herein are general in nature and are not intended to be, nor should be construed to be, legal or tax advice to any particular individual. Accordingly, individuals should consult their own legal or tax advisors for advice with respect to the tax consequences to them, having regard to their own particular circumstances.. Richardson GMP Limited is a member of Canadian Investor Protection Fund. Richardson is a trade-mark of James Richardson & Sons, Limited. GMP is a registered trade-mark of GMP Securities L.P. Both used under license by Richardson GMP Limited.