In Part 2 we consider risk from a retiree’s perspective and why they may not, quite reasonably, always follow economic theory.

Expected Shortfall

In Part 1 we considered shortfall risk; the possibility that your investments fall short of target at the end of an accumulation period. We considered a lower bound that investments should at least outperform cash.

Retirees are particularly concerned about shortfall risk because of the risk of running out of money when withdrawing from their nest egg. There is some evidence that people worry more about running out money in retirement than death[1]. This isn’t helped by financial commentators who, with dramatic flourish, talk about the probability of ruin in retirement. Canada provides some income security for retirees through the Canada Pension Plan (CPP) and Old Age Security (OAS), although most readers would be disappointed to have to rely on this exclusively in their retirement.

The other shortcoming of using the probability of ruin as a performance measure is that retirees are more concerned about dollars than probabilities; you can’t buy groceries (or a cruise) with probabilities. It is of little use saying that there is a 20% probability of running out of money. You could be short of $100 or $100,000; it would be helpful to know.

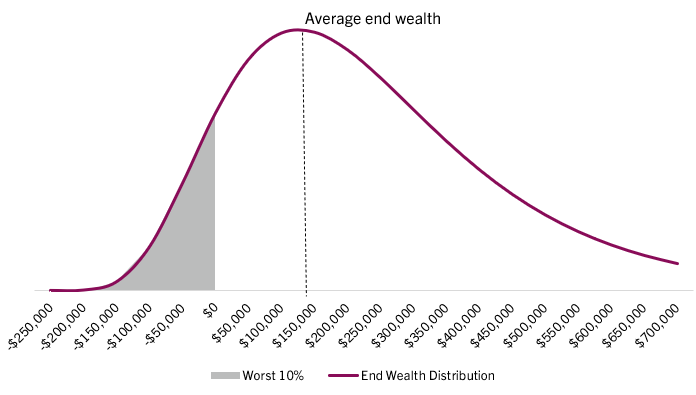

We prefer a measure, expected shortfall (ES), that includes both the probability and the cost of shortfall. Imagine you run 1000 scenarios of your 30-year retirement plan sampling monthly returns from historic data. You rank the scenarios based on your wealth at the end of the 30 years. The wealth distribution will look like the curve in Figure 1. The average of the worst 100 results (10% of all the scenarios) yields the expected shortfall. The illustration shows the average end wealth of all the 100 scenarios of $150,000 but the average of the worst 10 % (the shaded area) is an ES of -$50,000.

Figure 1: End Wealth Distribution

A homeowner might consider this ES is an acceptable risk if they are willing to dip into their house equity as a contingency against poorer than expected market returns.

ES illustrates and quantifies the risk, in dollars not probabilities, of a shortfall in retirement income. Most people need market exposure to get the growth required to fuel their retirement so some risk of shortfall is unavoidable. They also need a way of tracking the shortfall risk which ES handily provides. Although ES is useful to avoid a retirement shortfall retirees have a number of competing and shifting concerns.

The risk of underspending?

Can spending less than you saved make you happier in retirement?

A 2018 study[2] surveyed how U.S. retirees spending changed with age. Some of the key findings:

- Retirees decumulate their assets very slowly. Retirees that started with $500,000 or more had spent only 11.8% of the initial portfolio during the first 20 years.

- Those with the most money had the slowest rate of decumulation.

- About one-third of retirees had increased their assets over the first 18 years of retirement.

On this and other evidence, retirees are reluctant to see their retirement capital shrink. This could be a fear that they will eventually run out of money and, in the absence of any other strategy, preparing to live forever offers some protection. It might be expected that retirees who had income from a pension for life as part of their total income would feel more confident about drawing down their investments. This was not the case; the study found that retirees who had part of their income from a pension were less likely to reduce investment assets, despite a reduced risk of running out money. This suggests that the retirees were doing mental accounting – distinguishing between “income” dollars from their pension from “capital” dollars in their investment accounts. From this perspective the more stable income they had from the pension the less need they saw to draw from their investments. It is no surprise that a popular strategy is to rely on dividend stocks to generate retirement income.

Dividend Stocks

In his book[3], Meir Statman relates the story of Con Edison, a US utility that suspended their dividends. At the shareholder’s meeting many retirees expressed their distress with one shareholder speaking on behalf of another saying “ ..now she will get only one check a month and that will be her Social Security, and that she’s not going to make it, because you have denied her that dividend.”

An economist would be puzzled by this, knowing that there is no economic difference between a dollar from a company paid dividend or a dollar created by selling stock. Cash dividends from companies are paid from the capital of the company, which declines after the dividend is paid. It is a mental accounting error to treat dividends as income that can be paid, as if by magic, independent of the underlying capital.

But the economist would also be making a mistake to not appreciate that separating income from capital encourages self-control in the form of imposing a spending rule that limits the encroachment on capital and reduces the risk of outliving your capital (longevity risk). The conclusions from a study[4] of why retirees spend the way they do concluded that about 60 percent didn’t want to spend a significant portion of their assets for a variety of reasons:

- 27% feared running out of money.

- 38% percent were worried about unforeseen costs later in retirement.

- 37% didn’t feel the need to spend more.

- 33% wanted to leave money to heirs.

- 31% simply felt better when the account balance was high.

Running out money was a concern but not the dominant concern. 64% of survey respondents agreed that saving as much as they could made them feel happy and fulfilled.

The survey reminds us that sound advice rests on understanding the specific needs of the client, rather than assuming they want to maximise a purely economic objective. Settling on appropriate risk measures can be highly individual and evolve over time. Some objectives may conflict; for example, a desire for more reliable income might suggest an annuity which reduces the ability to leave money to heirs. This makes effective risk management a dialogue between advisors and clients where shifting priorities may require different risk metrics.

And not everyone has a happy retirement. The same survey found that high debt, for example, was associated with lower life expectancy, higher costs and dipping into savings during poor markets.

Surveys and mathematical models necessarily talk in terms of the collective or average experience. If you are an insurance company providing annuities then it makes perfect sense to estimate payouts based on mortality weighting – meaning that they expect the aggregate annuity payout decreases with age. Yet retirement is an individual experience that we plan to live in full and mortality weighting that reduces payouts with age makes no sense. Retirement planning should also be managed individually without relying on the rules that only work on average.

A final word about risk

In aggregate we manage our financial affairs to smooth out long-term consumption. We save to replace employment income and smooth out large expenses such as houses by borrowing. Ken French, a long standing research collaborator with Eugene Fama on how markets work, describes risk as “uncertainty about lifetime consumption[5]”.

As French points out, the risk of not sustaining future consumption is not primarily about the portfolio at all but how the portfolio interacts with the other sources or uses of future wealth such as pensions, job prospects, family dynamics and health. This broader idea of risk, when the cost of making a bad choice is high, speaks to the need to integrate portfolio management with sound financial planning encompassing the breadth of household wealth and risks. A topic for future discussion.